Dead Letter Department #120

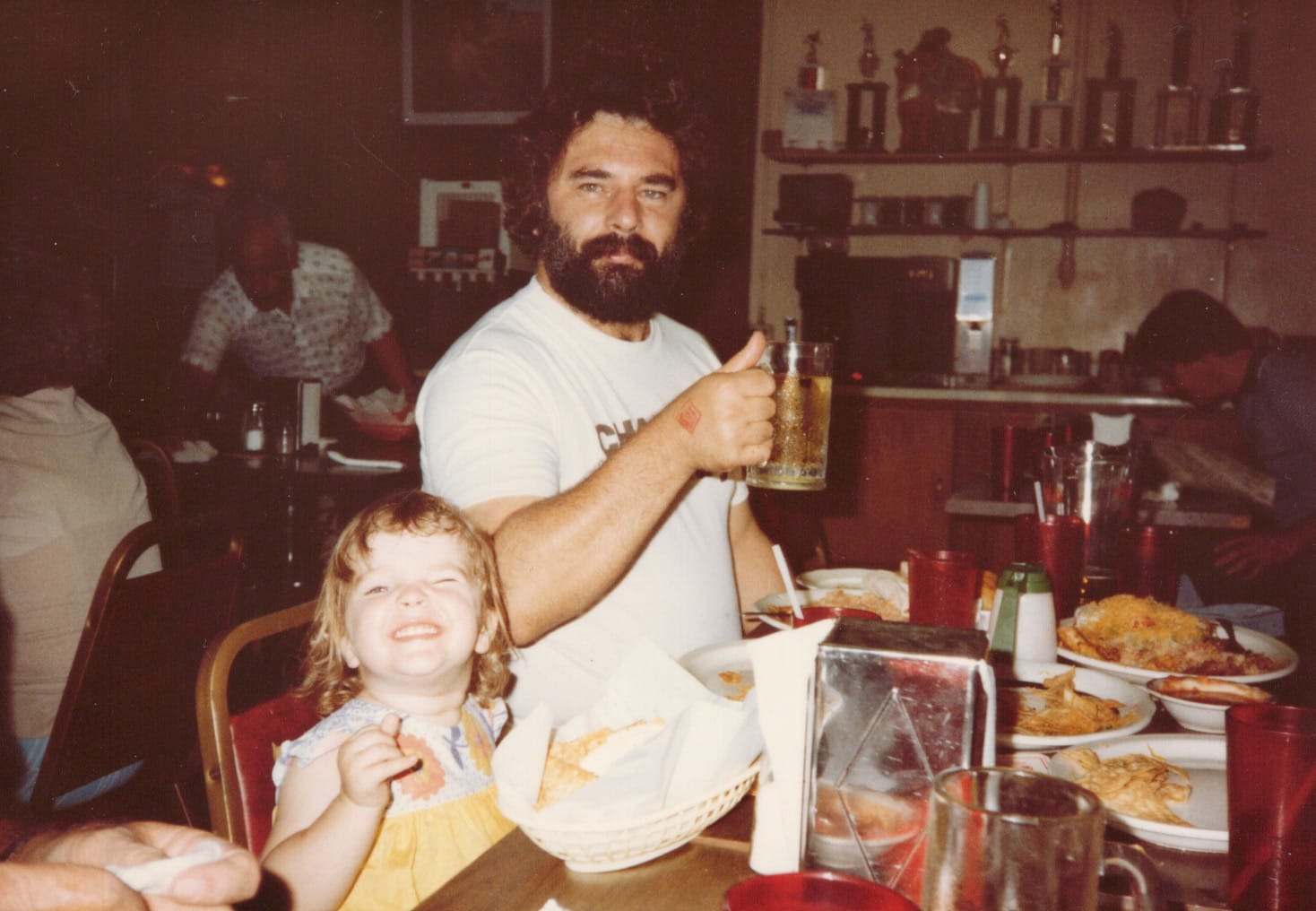

what my father ate

Clambakes on the beach as a kid, with all of his mother’s relatives, and chickens his Uncle Chick & Aunt Henry raised on their property, where I remember marveling at the full grown pines Chick told me he planted himself, back in the day, and eggs, of course. I imagine him going to lunch with my grandmother, tall & lovely, stylish from her years working at the George Fox department store, and dinners with his Aunt Charlotte & Uncle Pooley, but he wasn’t really one for remaking his childhood favorites, plus they were broke enough that I got the sense that the unlimited food at the fraternity at college was a bit of a novelty.

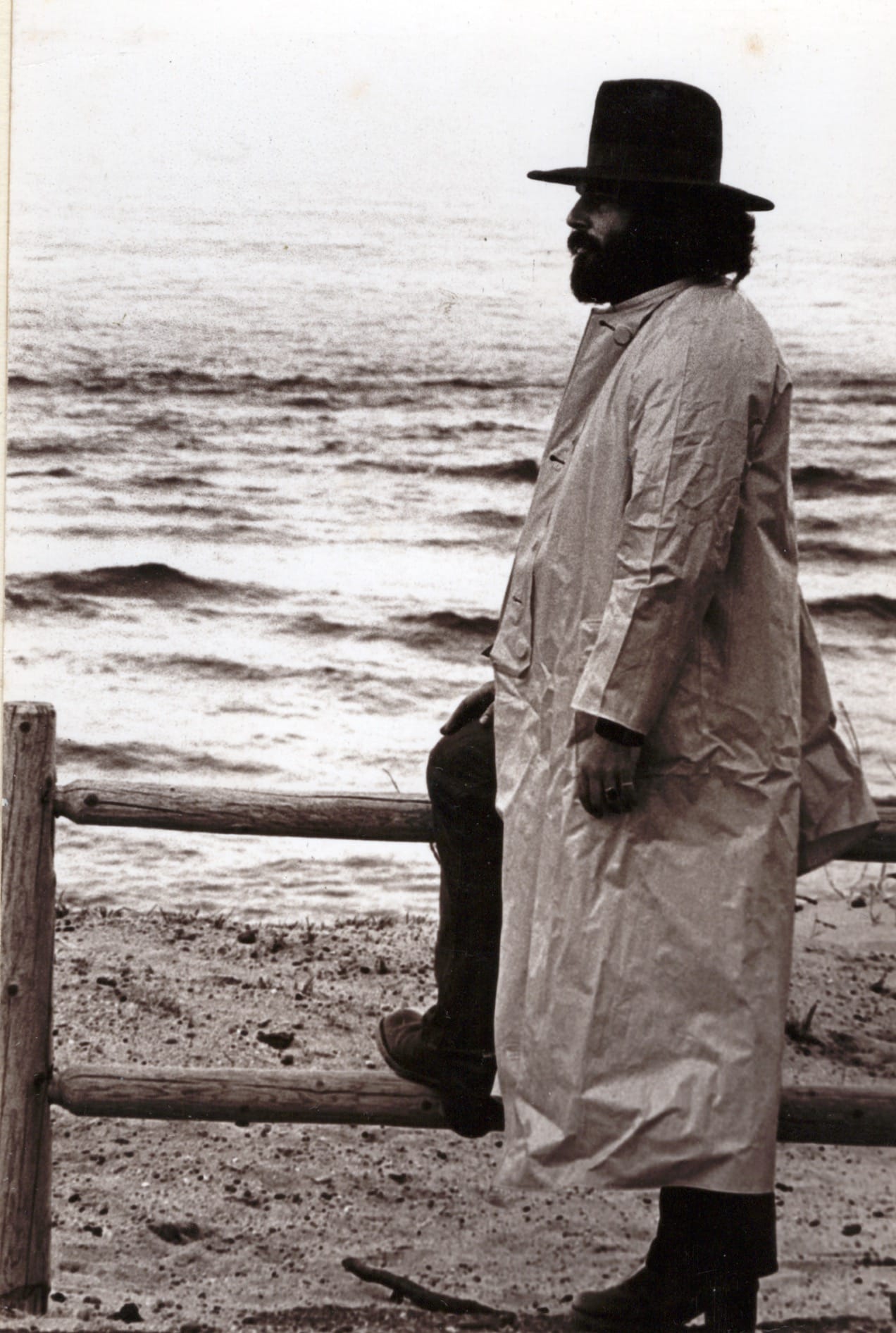

The picture sharpens a little for me after that: the Peace Corps in Peru, and then married to Doris, whisking around Europe to fancy hotels while she was on buying trips to set the cultural standard for fashion back home in New York. He had his haunts: Italian restaurants down in little tiled grottoes, the bar where Dylan Thomas drank, the hookup for illegal Cuban cigars, which he started, briefly, smoking when he quit cigarettes, inadvertently jacking his daily cost per day for tobacco from 50 cents up to about two dollars. They’d figured out, somehow, that the lights on 5th Avenue were timed for traffic to move at 25 miles an hour, which meant if you drove 50 late at night you could make every single green, and I have an image of him, windows open to city noise & lights, the other figures blurry, a cloud of fragrant smoke around his head as they sped through the city. He was always proud of having been a New Yorker, of knowing & loving the city.

And then my mother. In Connecticut, they lived in a barely renovated cabin on a lake, and the freeze was so hard they could walk right across the lake to go to their neighbor’s parties. Outside Boston, there was an enormous storm, a whiteout, shutting down the streets, but they were young & in love & stumbled off the T to the neighborhood bar instead of finding their way home, while the corner store owner risked fines by the city to be open, to make sure everyone could eat while the blizzard lasted.

In Arkansas my mother says the Sunday breakfasts were so enormous you could smell them from the next house: biscuits & gravy, bacon frying up, sausages. They had goats but not quite long enough to make cheese, and I think this is where the lifetime love of barbecue began. He & Don tried to get to every barbecue joint in Kansas City, and managed to make quite a dent. I’m sure it’s in his notebooks, the best ribs, the best brisket, and how much those two loved each other, all the way through my dad’s life.

Then Kansas, and the beginning of family of four traditions: donuts on Easter morning and sunrise at the river, wooden bowls of nuts around the house in the winter, sweet potatoes with raisins simmered in Grand Marnier at Christmas, black olives in the crystal dish at Thanksgiving.

I don’t remember when he decided to take over cooking dinner, but he said it was so nice to come home & have a solvable problem: what to cook, for four relatively unfussy people, which would then be eaten & tidied away; finished, unlike interminable work projects, endless negotiation. That was the beginning, in my mind, of eggs and chorizo, spicy fragrance filling the whole house, clam fettuccine in the big bowl. The microwaved vegetables we will leave, charitably, to one side, though their texture lingers in my memory.

Albuquerque was tamales, home made in enormous holiday batches or bought, and the smell of the Hatch chilis roasting in huge barrels outside the grocery store at the same time the roads were being repaved: spice & asphalt mixed together. There were limeades at the local fast food joint, and Mexican food at Sadie’s, where we sat up above the bowling alley & pulled great puffs of honeyed sopapillas apart with our fingers while the pins crashed to the floor. Fry bread at the festivals, prickly pear at the grocery store, candles in the birthday cakes.

In California we slid right into the bougie food scene, the indelible funk of the bulk food section at the co-op, home made granola, the tiny sushi joint where the plates went by on boats, the Italian restaurant with beef carpaccio & chocolate torte for special occasions. I remember the Christmases here more clearly, in their more finished ritual form: arguments about the texture of gravy, which his mother fussed over, and little triangles of rolls puffing up, pecan & pumpkin pies, with hand-whipped cream ‘to cut the richness,’ which was a joke, of course, and which I think of whenever I put whipped cream on pie, cranberry sauce sliding out of the can with a squelch. There was always stuffing in the fridge afterwards, for leftovers, and that might have been the best part.

I didn’t really realize, when we moved there, that Connecticut was essentially a return for him, close to where he was raised. New Haven had thin crust pizza and enormous tin foil tubs of Puerto Rican food, rice and beans & fried plaintains. There was the Italian deli in Fairfield, where we got curly squiggles of pasta, red sauce, & house-made sausage in two levels of heat, the perfect arancini, which I have never found since, big black & white cookies, and the restaurant near the seawall, with clam pizza and fettuccine alfredo.

That was when our New York tours commenced, stepping down into low lit restaurants, buying a little bag of sugared roasted chestnuts on the way back to the train after the theatre, dipping scallion pancakes into soy sauce, huge sandwiches at Katz’s and challah french toast at B&H Dairy, so cramped you crashed into other customers all the way to your table. Lobster rolls & clam chowder at the Cape, the place with fried scallops where we’d stop to meet his mother on the way—the name is on the tip of my tongue but I can’t quite reach it.

He had a nose for the best ice cream place, and always had a favorite, in California, in Connecticut, on vacation, and he could find the right taco truck in a cluster of options, the best little deli, shabby from the outside, that had stood for fifty years. In the early days of his retirement, when my parents were still together, I remember cocktail hour at their house, sharp cheese & crackers, castel vetrano olives, beers that were always too dark for me, dinners at Anthony’s, where his thrill of being able to take us to a white tablecloth restaurant any night of the week never quite faded. Before Casa Que Pasa closed, we went for huge burritos & little flautas & the best margaritas ever. He loved a dive, a place with slightly sticky floors & wonderful food.

The next era was new love, new tradition, new family. He wrote to me about lilikoi pie in Kauai, shopping for prepared foods at the big fancy delis in London, favorite restaurants in Astoria, on the way to the Oregon Coast, or at the Shakespeare Festival. I got pictures of sunsets & portrait shots of his shadow, letters & postcards afterwards, went to the Korean restaurant in town to meet his grandchildren, met him & his wife at Old Town dozens of times.

One of our last solo meals together out in the world was at Drayton Harbor: a massive tray of oysters, a pile of bread, and a slightly wobbly walk on the beach afterwards. The other was at Structures, where he went crazy for home made potato chips, & hot honey on his fried chicken sandwich.

After that it gets sadder, & I’ve written here before of bringing him little snacks at memory care, sitting with him in the facility cafeteria trying to coax him to eat, piling blueberries onto his plate. I’ve written about his favorite chocolate ice cream, at the very end of things, optimistically buying him two pints.

I think of him when my friend & I order grilled oysters at the SeaFeast, and when I sit against the glass on a blustery day & eat fried fish; I think of him when I make sure the pasta is al dente; when I crush the olive with the flat of my knife, or mince the garlic; when I put salmon over green salad.

Today is one year exactly. I still have the second pint in my freezer, completely inedible by now, I am sure, but I haven’t been able to throw it away.